Did Social Data Predict the Winner of the London Mayoral Election?

A couple of months ago I penned a blog post looking at the London Mayoral election and seeing if there was any correlation between what was being discussed online, the sentiment expressed and the actual result.

A couple of months ago I penned a blog post looking at the London Mayoral election and seeing if there was any correlation between what was being discussed online, the sentiment expressed and the actual result.

I put my hands up at the time and said the methodology could have been (greatly) enhanced, that the online population is not reflective statistically of the electorate, as well as there being many unknown factors. If truth be told I was more interested in testing the hypothesis that online conversation offers insight into offline behaviour, rather than the subsequent party political conversation which followed.

Anyway, back to the hypothesis. Based on the data I collected it looked like Boris might emerge with a victory of between 8-13 points, but in actual fact the result was a lot closer. For those who can’t recall the numbers; the final result saw Boris Johnson win by 4 points having received 44% of the vote, with Ken Livingstone on 40% and Brian Paddick 4%, whilst the various independent candidates received 12% of the votes cast.

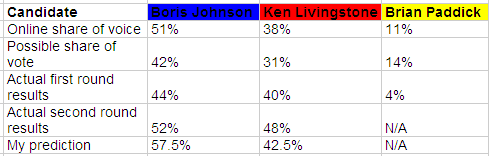

Here’s a chart showing the online share of voice, possible share of vote, the actual results and of course, my predictions.

Based on share of voice from the social data, Brian Paddick was undoubtedly the biggest loser as his 11% share only translated into a disappointing 4% of the actual vote. His campaign team will surely be left wondering how they failed to resonate with the electorate.

Based on share of voice from the social data, Brian Paddick was undoubtedly the biggest loser as his 11% share only translated into a disappointing 4% of the actual vote. His campaign team will surely be left wondering how they failed to resonate with the electorate.

Interestingly, the possible share of the vote which I calculated based on the level of positive online conversation for each candidate in relation to share of voice gave Boris Johnson a 42% share of the vote, Ken Livingstone 31% and other candidates 27%.

The reality was that when the second round votes had been counted, Londoners had given Boris 52% of the vote versus Ken’s 48%. Admittedly, the predicted figures of Boris’ 57.5% and Ken’s 42.% are not earth-shatteringly accurate, but nor are they wildly off target and the winner, albeit a favourite was correctly predicted.

So, what can we conclude from this quick and dirty experiment? Did social data predict the winner? Can we use it for future elections? These questions are difficult to answer – especially without further research. However, two improvements do immediately spring to mind; the experiment would benefit from a more developed methodology and weighting the online share of voice against the number of internet users in London to give a more accurate representation.

Whilst, social data is not a full or accurate portrayal of public opinion, it does offer some indication from which we can draw valuable insight. Indeed, when the margins are so marginal the strength of an indication, much like a political opponent should not be underestimated.